Welcome to Part 4 of our series on veganic gardening. Click here to see the whole series. Subscribe to this blog to make sure you don’t miss future posts.

How does your garden grow? Do you know?

Above-ground, plant leaves practice the magic of photosynthesis, transforming sunshine into edible calories. Flowers burst from buds and then fruits burst from flowers. But, as is so often true, much of the action that drives these dramatic changes takes place out of sight. Below-ground, plant roots probe the earth, stretching out in search of vital nutrients. Earthworms and other underground animals tunnel, simultaneously aerating and fertilizing along the way. Rocks break down. Remains decay. Microbes teem, recycling everything.

In short: Your garden soil is (or should be) alive, and this life makes the above-ground growth possible.

Organic gardeners of all varieties know: Everything depends on the living loam. Organic gardeners take care of the soil upon which plants depend for sustenance. Unfortunately, in seeking to nurture their own soil, some organic gardeners sometimes turn to products of animal exploitation.

Veganic gardeners also respect the soil, including the animals who help to co-create it, and thus join organic gardeners in focusing on promoting natural soil health through routine practices and in shunning synthetic fertilizers and pesticides in favor of organic remedies when it becomes necessary to intervene in problems. But veganic gardeners don’t see the point in protecting one’s own garden while contributing to the pollution of somebody else’s home, and thus shun products of factory farming, such as manure or feather meal. Veganic gardeners respect all animals—not just earthworms—and thus choose plant- or mineral-based soil amendments rather than products of animal exploitation, such as bone meal or blood meal.

Don’t worry! Veganic alternatives to such gruesome products are readily available. Even more importantly, routine care of healthy soil makes extreme interventions unnecessary. If your garden soil is not badly imbalanced or damaged in some way and you take good care of it every year, then you won’t ever need the information at the bottom of this post.

The key to keeping healthy soil happy is compost. Compost, compost, compost. I’ll say it again: Compost.

Can you guess the solution to many soil problems? You’ve got it: Compost, along with other organic matter.

Soil consists of water, air, and minerals as well as organic matter such as decomposed plant matter, insect excrement, and a truly amazing array of microbes. You might be surprised by how much of what you think of as earth is actually air and water. This brings up an important point: Both plant roots and underground fauna need both air and water. Thus, healthy soil both holds water and drains well. Water, whether from rainfall or a garden hose, should be retained long enough to let everybody have a drink but should eventually drain away.

Soil consists of water, air, and minerals as well as organic matter such as decomposed plant matter, insect excrement, and a truly amazing array of microbes. You might be surprised by how much of what you think of as earth is actually air and water. This brings up an important point: Both plant roots and underground fauna need both air and water. Thus, healthy soil both holds water and drains well. Water, whether from rainfall or a garden hose, should be retained long enough to let everybody have a drink but should eventually drain away.

The percolation test and the watering test are easy ways to see if your soil is draining too slowly or quickly. To test for slow drainage, dig a hole that is a foot deep and half a foot wide; fill the hole with water and let it drain; fill the hole with water again and walk away, coming back to check regularly—if it takes more than 8 hours to empty, you’ve got a problem. To test for overly rapid drainage, water an unplanted area of your garden bed very well; 48 hours later, dig down six inches—if it’s dry, you’ve got a problem.

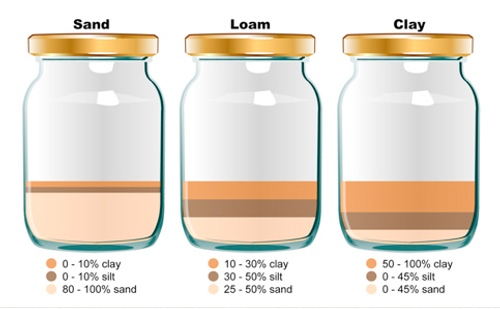

Drainage problems may be due to the constitution of your soil. The mineral content includes silt, sand, and clay. The proportion of sand to clay determines drainage: Too much sand, and the water runs right through; too much clay and it doesn’t drain quickly enough. One fun way to see if your ratio of silt, sand, and clay are in the healthy range is the jar test. Put a handful of soil into a jar of water and then set it in a still place for a day to let it settle. The organic matter will float to the top. Down at the bottom, you will see strata of sand, silt, and clay, as follows:

The ideal garden soil is loam—a balance of the three. If you have slightly more than idea sand or clay, that’s OK. (I actually prefer a slightly sandy soil myself, for various reasons.) But if your jar looks like those on the left or right, then you may see problems. Overly sandy soil can’t hold water and thus also can’t hold water-soluble nutrients that plants need. Clay soil may smother plant roots and also drains poorly. The solution to both of these problems is—you guessed it—compost and other organic and mineral matter. To augment sandy soil, you want material that holds onto moisture. To augment clay soil, you want material that will help to aerate the soil.

Drainage problems also can be caused by soil compaction, as may happen in an area that has been heavily trafficked, or other damage to the structure of the soil. Warning! Never, ever dig in your garden when it is wet. One day of wet digging can damage soil structure so badly that years of recuperative efforts will be necessary. Also avoid over-tilling, which can also damage soil structure. Dig or till only as much as is absolutely necessary to prepare the ground for planting—and, again, never do so when the soil is wet, or you will end up with clumpy lumps of inert dirt rather than the living loam your plants crave.

Besides providing long-term help in maintaining and correcting soil structure, compost serves as fertilizer. When you turn over your soil before planting, you can dig or till in well-ripened compost, as well as well-dried leaves or grass cutting left over from fall. (Save any fresh clippings to use as mulch later in the season.) If you don’t compost yourself, think about starting to do so. (We’ll offer some tips in a future post.) Meantime, see if yourtown or city is one of the growing number that make composted yard and/or food waste available to the public. If not, check out your local food co-op, organic gardening store, or anyplace else where you typically see seedlings for sale in the spring.

Unless you have some sort of nutrient deficiency, compost ought to be the only fertilizer you need. How do you know if you have such a deficiency? You could pay for a fancy soil test, but unless you have some reason to believe that your garden soil is likely to be deficient in some nutrient, I suggest just putting in a garden and letting observation be your guide. What might make you think that your soil is depleted? Perhaps you know that the same crop was grown on it, year after year, without replenishment. Or perhaps you know that the previous person who gardened there doused the soil with chemicals, thereby probably killing beneficial soil fauna. Maybe you gardened there last year and noticed problems. For example, if your plants were producing abundant greenery but only scant flowers and fruits, then you’ve got plenty of nitrogen but may be short of phosphorus. On the other hand, plants that are trying to flower, even though they’ve not got nearly enough leaves, suggests a nitrogen deficiency.

What’s all this about nitrogen and phosphorus? Those are two of the three key plant nutrients, the third being potassium. Bagged organic fertilizers provide these three nutrients in the right balance, but often rely on animal parts or products for the nitrogen. Compost is also a well-balanced overall fertilizer, so that should be the veganic gardener’s go-to choice for fertilizers. In addition to being dug in before planting, well-decomposed compost can be “side-dressed” into the garden during the growing season. “Compost tea” can even be squirted directly on plants.

More on mid-season fertilizing later. For now, let me just provide some veganic alternatives to common soil amendments in case you find yourself needing to deal with a known deficiency of a particular nutrient in your soil.

Nitrogen: cottonseed meal, soybean meal, alfalfa meal, composted (not fresh!) coffee grounds

Phosphorus: rock phosphate, colloidal phosphate

Potassium: wood ash, kelp meal, seaweed, greensand

Our veganic gardening series will continue through the year. (If you liked this entry, you’ll be especially interested in our fall tips for returning nutrients to the garden.) Stay tuned.

Leave a Reply